La teosofia

L’occultismo era fiorente nella Vienna di fine secolo quando Mahler aveva circa quarant’anni.

Nella Vienna di fine secolo c’era molto di più di quanto non appaia agli occhi degli studiosi. Oltre ai tipi di figure e argomenti che tendono a rafforzare le aree di indagine “legittime” – ad esempio la filosofia, l’architettura musicale e la psicoanalisi – a Vienna, come in gran parte del mondo di lingua tedesca, era presente un sottosuolo occulto. Si trattava di un mondo in cui la teosofia, l’antroposofia, il pitagorismo, l’astrologia, la chiaroveggenza, la numerologia e altre forme di credenze occulte giocavano un ruolo – e a volte un ruolo importante – nella vita di alcuni degli stessi personaggi che compaiono spesso negli scritti sulla Vienna di fine secolo.

Nel suo libro Hammer of the Gods, David Luhrssen include Mahler come membro della Società Teosofica di Vienna.

I membri originari della Società Teosofica di Vienna, alla sua fondazione nel 1887, provenivano da un gruppo di intellettuali e bohémien che si riunivano continuamente dalla fine degli anni Settanta del XIX secolo. Frederick Eckstein (1861-1939), primo presidente della Società e in seguito “eminenza grigia della vita culturale viennese”, aveva presieduto le discussioni a un tavolo di un ristorante vegetariano viennese per un decennio prima che la Società fosse formalmente organizzata nella capitale austriaca.

La cerchia di Frederick Eckstein (1861-1939), che era stato segretario personale di Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), era varia per origine etnica e politica. Ne facevano parte il poeta polacco Siegfried Lipiner (1856-1911), il maestro sinfonico ebreo Gustav Mahler, il compositore austriaco di canzoni d’arte tedesche Hugo Wolf (1860-1903), la femminista Rosa Mayreder, che discuteva i ruoli di genere in termini di fusione alchemica degli opposti, Rudolf Steiner, che in seguito fondò il movimento della scuola Waldorf insieme a un ramo mistico-cristiano della Teosofia chiamato Antroposofia e, occasionalmente, Victor Adler (1852-1918), fondatore del Partito Socialdemocratico d’Austria.

Tuttavia, in Storia del modernismo, Bernard Smith indica che Alma Mahler divenne teosofa nel 1914, tre anni dopo la morte di Mahler, e le viene attribuito il merito di aver introdotto alla Teosofia Johannes Itten, un pittore espressionista svizzero. Sebbene Mahler avesse un interesse per l’esoterismo, non è chiaro se Gustav Mahler stesso sia diventato un teosofo o sia stato effettivamente un membro della Società Teosofica di Vienna.

Johannes Itten (1888-1967), che insegnò al Bauhaus dal 1919 al 1923, si interessò alla teosofia dopo aver conosciuto la prima moglie di Walter Gropius, Alma Mahler, teosofa dal 1914. Lesse Forme di pensiero di Besant e Leadbeater, la Filosofia indiana e la Cabbala e sposò il punto di vista della setta Mazdanan, che insisteva sulla meditazione e sul vegetarianesimo.

Tuttavia, negli ultimi mesi prima della sua morte, Gustav e Alma condivisero l’interesse per la letteratura teosofica.

Mahler si prodigò nel tentativo di dimostrare ad Alma il suo affetto. La invitò alle cascate del Niagara e in generale fu più affascinante e attento di quanto fosse mai stato prima. Almeno all’inizio, questi ultimi mesi non furono troppo oscurati, se non da problemi con l’orchestra. La coppia iniziò a interessarsi alla teosofia e all’occulto e studiò i libri di C. W. Leadbeater e Annie Besant, quest’ultima ex collaboratrice di Helena Blavatsky, che erano le dernier cri in Europa e in America.

Nel suo libro Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters, Alma Mahler conferma l’interesse della famiglia Mahler per l’occulto.

Vedevo molto una giovane donna americana che cercava di impregnarmi di occultismo. Mi prestò libri di Leadbeater e della signora Besant. Appena se ne andava, andavo sempre da Mahler e ripetevo parola per parola tutto quello che mi aveva detto. Era una novità per quei tempi e lui era interessato. Cominciammo a chiudere gli occhi per vedere quali colori riuscivamo a vedere. Praticavamo questo – e molti altri riti ordinati dagli occultisti – così gelosamente che una volta Anna Justine Mahler (Gucki) (1904-1988) fu scoperta a camminare su e giù per la stanza con gli occhi chiusi. Quando le chiedemmo cosa stesse facendo, rispose: “Sto cercando il verde”.

John Covac ipotizza che i Mahler stessero leggendo il libro di Leadbeater e Besant Forme di pensiero.

Nel caso di questo aneddoto, il libro in questione è molto probabilmente Forme di pensiero di Leadbeater e Besant, che discute i significati spirituali dei colori in termini entusiasticamente teosofici.

È più probabile che la famiglia Mahler abbia appreso a “vedere” il colore verde leggendo la sezione sulla percezione del capitolo intitolato Note su alcuni insegnamenti orali nel “terzo volume” (volume 5 nell’edizione di Adyar) de La Dottrina Segreta, pubblicato da Annie Besant nel 1897:

Cercate di immaginare qualcosa che trascende il vostro potere di pensiero, per esempio la natura dei Dhyân Chohans. Allora rendete il cervello passivo e passate oltre; vedrete una luce bianca e radiosa, come l’argento, ma opalescente come la madreperla; poi ondate di colore passeranno su di essa, iniziando dal viola più tenero, attraverso sfumature bronzee di verde fino all’indaco con lucentezza metallica, e quel colore rimarrà. Se vedete questo, siete su un altro piano. Dovreste passare attraverso sette stadi.

Quando arriva un colore, guardatelo e se non è buono rifiutatelo. Lasciate che la vostra attenzione si fermi solo sul verde, sull’indaco e sul giallo. Questi sono colori buoni. Poiché gli occhi sono collegati al cervello, il colore che vedete più facilmente sarà il colore della personalità. Se vedete il rosso, è solo fisiologico e va ignorato. Il verde-bronzo è il Manas inferiore, il giallo-bronzo l’Antahkarana, l’indaco-bronzo il Manas. Questi vanno osservati e quando il giallo-bronzo si fonde con l’indaco si è sul Piano Mânasico.

Fin de siècle è il termine francese per indicare la fine del secolo.

Covach, John, Balzacian Mysticism, Palindromic Design and Heavenly Time in Berg’s Music, Encrypted Messages in Alban Berg’s Music, ed. Siglind Bruhn Routledge. Siglind Bruhn Routledge (New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998).

Luhrssen, David, Hammer of the Gods: The Thule Society and the Birth of Nazism (Washington, D.C., Potomac Books Inc., 2012) p. 13.

La Staatliches Bauhaus, comunemente nota come Bauhaus, era una scuola d’arte tedesca che combinava artigianato e belle arti ed era famosa per l’approccio al design che pubblicizzava e insegnava. Ha operato dal 1919 al 1933. A quel tempo, il termine tedesco Bauhaus – letteralmente “casa di costruzione” – era inteso come “scuola di costruzione”. Il Bauhaus era stato fondato da Walter Gropius a Weimar.

Il Mazdaznan era una religione neo-zoroastriana che sosteneva che la Terra dovesse essere riportata a un giardino dove l’umanità potesse cooperare e conversare con Dio.

Smith, Bernard Modernism’s History, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press Ltd., 1998) pp.76-77.

la moda più recente.

Fischer, Jens Malte Gustav Mahler, tr. Stewart Spencer (Gran Bretagna: Yale University Press, 2011).

Anna Justine Mahler (15 giugno 1904 – 3 giugno 1988) era la seconda figlia del compositore Gustav Mahler e di sua moglie Alma Schindler. La soprannominarono “Gucki” per via dei suoi grandi occhi blu (Gucken in tedesco significa “sbirciare” o “fare capolino”).

Mahler, Alma Gustav Mahler: Memorie e lettere, a cura di Donald Mitchell, (New York). Donald Mitchell, (New York, Viking Press, 1969), p.188.

Covach, John, Balzacian Mysticism, Palindromic Design and Heavenly Time in Berg’s Music, Encrypted Messages in Alban Berg’s Music, ed. Siglind Bruhn Routledge. Siglind Bruhn Routledge (New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998) p.7.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna, La Dottrina Segreta, vol. V, (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, Inc., 1971), 554.

https://religion.fandom.com/wiki/Esotericism_in_Germany_and_Austria

Gustav Mahler in Vienna

The great composer and conductor, Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), lived in or visited Vienna at various times during his life. He also died here.

Use the info, links and map below to find your way to the more resonant sites associated with his work and music in the city.

- See also:

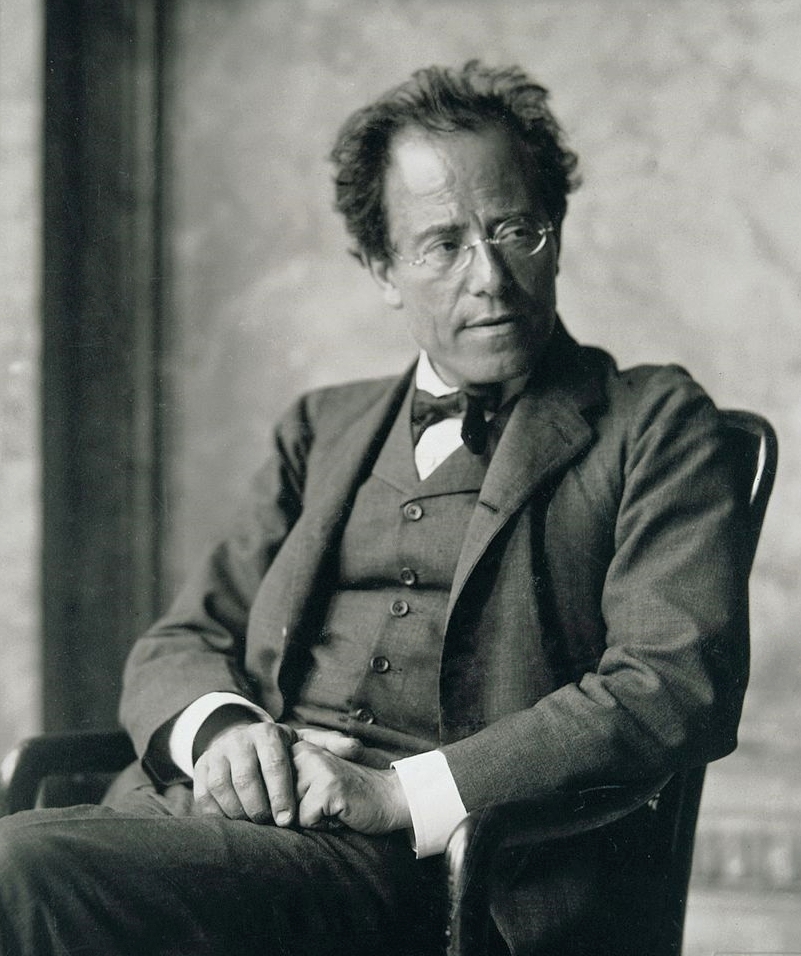

MAHLER: HIS LIFE

Mahler remains indelibly connected to Vienna through his tenure in charge of the State Opera House (Staatsoper), where he served as director from 1897 to 1907. Experts credit him with turning the Hofoper (as it was then called) into a world-class institution.

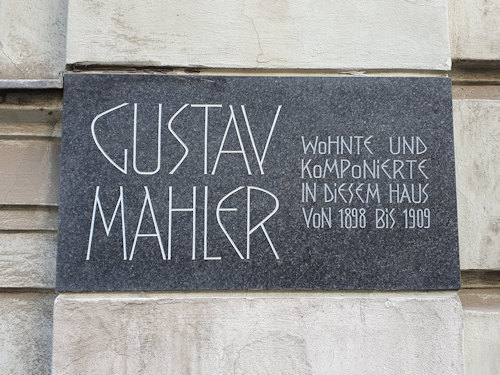

AUENBRUGGERGASSE 2

(A plaque reminds us of the famous resident)

Mahler lived for most of his time as director in an apartment on Auenbruggergasse opposite Lower Belvedere Palace.

Otto Wagner designed the building around 1890 and a small plaque outside reminds passersby of its one-time famous musical occupant. The text reads (my translation):

Gustav Mahler lived and composed in this house from 1898 to 1909

The architect built himself a home out in the woods in the late 1880s, where he also entertained guests that included Mahler and Gustav Klimt.

The Otto Wagner villa is open to the public as the Ernst Fuchs Museum. Little of the original interior survives, but the room known as the Adolf Böhm-Saal remains largely as it was in Mahler’s time.

KARLSKIRCHE

(The church also serves as a concert venue today)

The beautiful 1737 Karlskirche church towers over Karlsplatz square. Gustav Mahler married Alma Schindler here in 1902.

MAHLER’S DEATH

(A plaque marks the location of Mahler’s final day)

After a short period in the USA, a seriously-ill Mahler returned to Vienna from New York in May, 1911, and was taken immediately to the Loew Sanitorium in Vienna’s 9th district. He died there just a few days later on May 18th.

A plaque outside the building at Mariannengasse 20 commemorates the sad event. It simply says (my translation):

Gustav Mahler died in this house on May 18th, 1911

Below the statement and a brief line of music are the names of those who presumably organised the plaque: the city of Vienna, the Wiener Philharmoniker orchestra, and the International Gustav Mahler Society (whose premises and archives are in Vienna’s 4th district at Wiedner Gürtel 6/2).

MAHLER’S GRAVE

(The cemetery is out in one of the more upmarket suburbs)

The funeral took place on May 22nd at Grinzing cemetery in Vienna’s 19th district. Among the guests: Gustav Klimt and Arnold Schoenberg.

Mahler’s grave consists of little more than a large, plain stone block with a grassy patch in front. It’s not far from the cemetery’s main entrance and close to the grave of his wife, Alma Mahler-Werfel.

MAHLER: HIS WORK & MUSIC

THE STAATSOPER

(The rear of the opera house)

As well as introducing various reforms at the opera house, Mahler also worked on the creative side of operations.

The Hofoper performed his production of Beethoven’s Fidelio 35 times, for example, and he conducted at five of those.

One of the rooms where you can enjoy an interval drink is named after him (the Gustav Mahler-Saal). It houses, for example, a travelling piano that once belonged to the celebrated composer. A tour of the opera includes the Saal.

MUSIKVEREIN

(One of the world’s great concert venues)

Inevitably, Mahler performed at Vienna’s top concert venue during his time at the Hofoper: a bust inside the Musikverein pays tribute to this connection. Other names intimately connected with the location include Brahms and Bruckner.

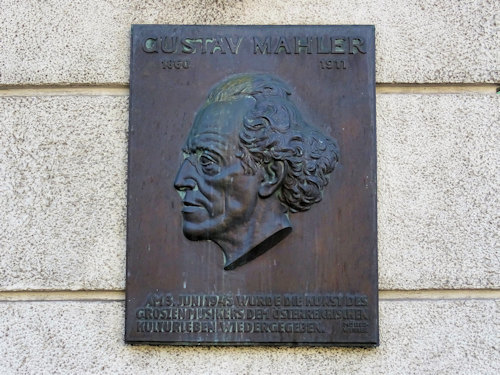

KONZERTHAUS

(Plaque as homage)

Although Mahler died before completion of the Konzerthaus, a 1945 plaque on the wall outside Vienna’s other major concert venue commemorates the “return” of his work to the city (my interpretation of the inscription) after the end of fascist rule in Austria.

The Nazis had previously deemed Mahler’s music as degenerate.

SECESSION

(The Secession from the Jugendstil era)

Mahler also conducted a brief arrangement of Beethoven at the Secession building for the opening of the celebrated 1902 Beethoven art exhibition put on by Gustav Klimt and colleagues.

Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze wall painting (still on view at the Secession) allegedly includes Mahler depicted as the Golden Knight.

MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTION

The Neue Burg wing of the Hofburg palace provides a home for the Historical Musical Instrument Collection, which forms part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum group of museums and collections.

One of the many keyboard instruments on display is a 1902 piano that belonged to Mahler.

MAHLER: MEMORIALS & MORE

MAHLER STAR

(A rather appropriate location)

The square immediately to the east of the Staatsoper has Mahler’s star embedded in the pavement (look opposite the fountain).

HAUS DER MUSIK

(View Mahler memorabilia within)

Think of the Haus der Musik as a museum of music and sounds. One floor has rooms dedicated to individual composers associated with Vienna, including one for Mahler.

As well as photos and other pieces of memorabilia, the museum has a score for the Marriage of Figaro with Mahler’s handwritten notes scribbled on it.

UPPER BELVEDERE PALACE

I spotted the famous bust of Mahler by Rodin among the artworks on the Klimt floor of the Upper Belvedere museum. Note that Belvedere rearranges its permanent displays at intervals, so I can’t guarantee it will always be there.

MAHLERSTRASS

(One of many streets here named after composers)

Pop out of the State Opera House’s east entrances and you find yourself opposite Mahlerstrasse, a street leading away down from Hotel Bristol (where Mahler once stayed) and along the edge of Vienna’s picturesque old town.

You might consider the street name representative of the entirety of Austrian history. Created in the late 1800s, it first bore the name Maximilianstraße, after the brother of the Emperor of the time.

Then in 1919, when Vienna began to disassociate itself from the now defunct Habsburg monarchy, the street became Mahlerstraße. Then it became Meistersingerstraße in 1938, named for a Richard Wagner opera (the Nazis at work, again), before reverting to Mahlerstraße in 1946 (shortly after Vienna’s “liberation” from the fascists).

Watch this space for more Viennese connections as I come across them…

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/embed?mid=1Wr2CZuoSpoi4LYicY0Uy7_TgyOXC1XnV

LAST MODIFIED: NOVEMBER 21, 2022

Ad:

ON THE TRAIL OF MUSICIANS

Search this website

(Accommodation search provided by Booking.com*)

DISCOVER VIENNA:

Visiting Vienna: an independent guide written by a local